A Day on Saint Kitts

The bus rolled higher and higher on the left side of the narrow hilly road. The blue Caribbean Sea sparkled below.

This post contains affiliate links. For more information, click here.

My cruise companions and I were taking a tour on the island of Saint Kitts, about 1,300 miles from Miami.

Christopher Columbus first sighted the island in 1493 and claimed it for Spain. But it was English and French settlers who began colonizing Saint Kitts early in the 17th century. Control passed back and forth between the two powers for more than a century.

In 1625, Samuel Jeffreson purchased land on Saint Kitts and started the island’s oldest sugar plantation. Jeffreson is believed to be a great-great-great-grandfather of America’s Thomas Jefferson.

A few decades later, Jeffreson sold the property to the Earl of Romney. In 1834, the sitting Lord Romney became the first plantation owner on Saint Kitts to free his slaves. Today, the modest plantation house hosts a batik atelier.

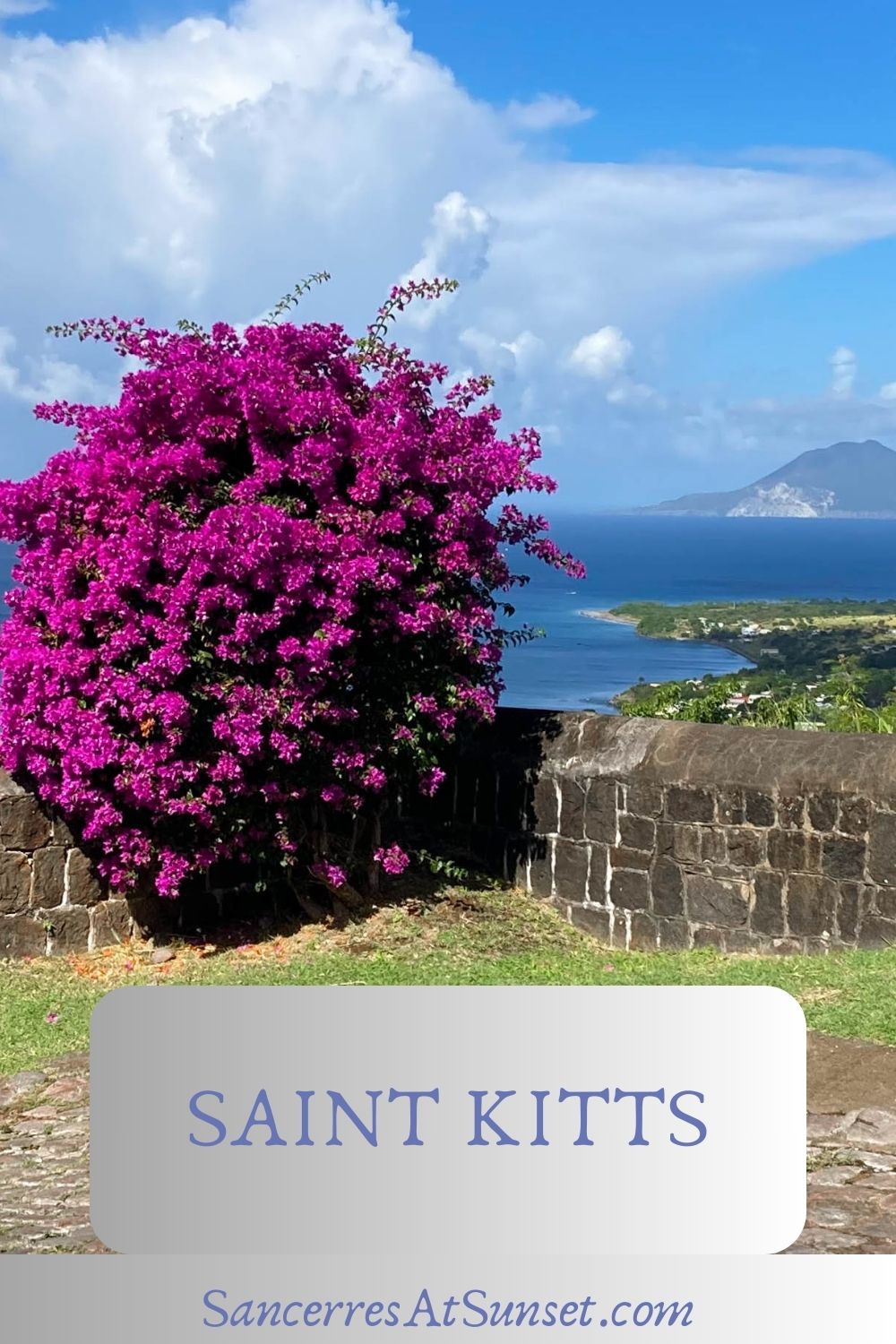

But the nearly eight-acre grounds feature the magnificent Romney Gardens, which combine Caribbean flora with European aesthetics.

The centerpiece is a 400-year-old Saman tree, which covers nearly half an acre. There are beautiful views of the Caribbean Sea. Wild chickens roam around the garden.

The garden also features the only known bell tower still in good shape on Saint Kitts.

Bell towers regulated the daily lives of slaves by signalling when to change activities. After emancipation, freed slaves often destroyed their plantation’s bell tower. But when Lord Romney freed his slaves early, they left the bell tower intact.

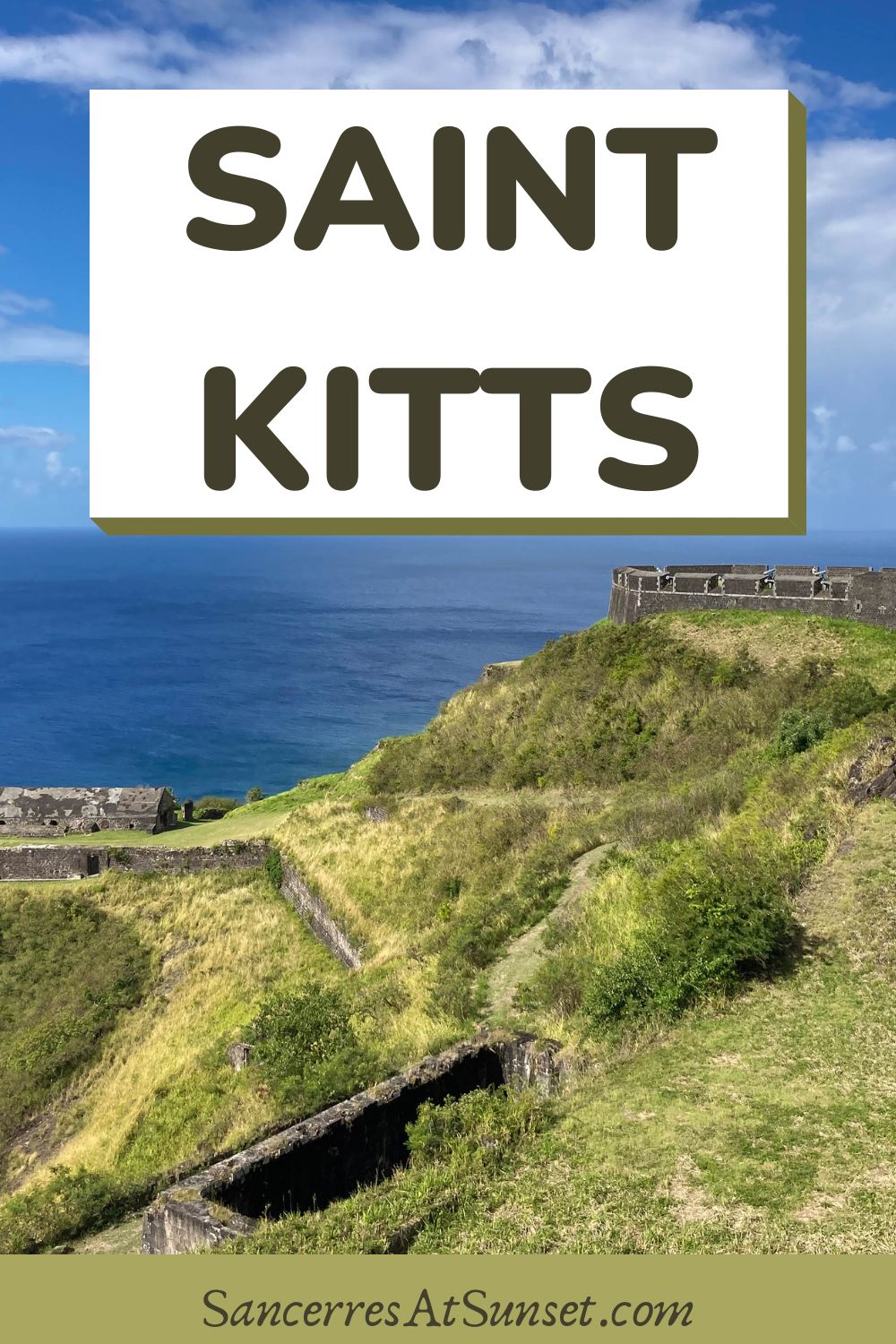

From there we headed to Brimstone Hill, where the British began building a fortress in 1690. Construction continued intermittently for a century.

The French attacked the fort several times over the next decades, seizing control near the end of the American Revolution. With the Treaty of Paris in 1783, France gave up control of Saint Kitts to Britain, though they did try to attack Brimstone Hill again during the Napoleonic Wars.

But by the middle of the 19th century, the British no longer needed the so-called “Gibraltar of the West Indies” and abandoned it.

In 1985, Queen Elizabeth II dedicated the area as a national park. Today the fort stands as recognizable ruins of limestone and volcanic rock atop a hill nearly 800 feet high.

We hiked up the steep pathway and explored the vast remains, including the bastions, the artillery officers’ quarters, and the reconstructed citadel. But the real draw is the magnificent views from the Fort’s strategic vantage points, high enough to see Saint Martin more than 50 miles away.

After the tour bus returned us to Basseterre, we decided to walk around the capital city before re-embarking our ship.

In the mid-18th century, Pall Mall Square became a central gathering place. Georgian architecture still surrounds it on three sides. Tragically, it was also the site of a slave market.

The British empire abolished the slave trade in 1807. Slavery itself nominally ended in 1834, though in practice what happened was closer to the gradual manumission envisioned by the Marquis de Lafayette; for the next four years, “freed” slaves continued to work for their “former owners” but for wages.

In 1983, the Federation of Saint Kitts and Nevis achieved independence from Britain, and Pall Mall Square became Independence Square.

A fountain now stands at the site of the auction platform.

Back aboard Nieuw Statendam as the day drew to its close, we sailed past the old British fort we’d visited earlier while the skies opened up to a familiar Caribbean rainstorm.

But then the sun started to shine through again, and we caught a glimpse of a rainbow in the clouds shrouding the island.

By the time the sun set, we were out to sea.

After my misspent youth as a wage worker, I’m having so much more fun as a blogger, helping other discerning travellers plan fun and fascinating journeys. Read more …

My beautiful paradise in the 🌞💙kittian gyal