Johnson Victrola Museum in Dover, Delaware — echoes of the past

We stepped through the red double doors and into the sounds of an earlier era.

This post contains affiliate links. For more information, click here.

The tightly packed Johnson Victrola Museum in Dover, Delaware, honors the mechanical and business genius of Eldridge Reeves Johnson, a pioneer in the music industry whose innovations transformed how we enjoy music.

The captivating small Museum is a visit to an earlier time, both simple and exciting, when the lingering philosophical ideas of the American Revolution and the scientific ideas of the industrial revolution melded together and sparked invention and innovation in a culture that prized uncapped opportunity.

As the founder of the Victor Talking Machine Company, Johnson helped develop and popularize the Victrola, a kind of phonograph that brought recorded music into homes worldwide. His work made music accessible and enjoyable for everyday people, revolutionizing entertainment in the early 20th century.

But not everyone recognized his potential early on. When Johnson graduated from the Delaware Academy at age 15 in 1882, the school’s director told him, “You are too God-d—-d dumb to go to college. Go and learn a trade.”

He did. After serving a five-year apprenticeship, Johnson became a machinist. By 1894, he had purchased his employer’s business and rebranded it as the Eldridge R. Johnson Manufacturing Company.

He was soon approached to design a spring-driven motor for the commonly used, manually driven gramophone, invented by Emile Berliner.

His first impression was mixed: “The little instrument was badly designed. It sounded like a partially educated parrot with a sore throat and a cold in the head. But the wheezy instrument caught my attention and held it fast and hard. I became interested in it as I had never been interested before in anything. It was exactly what I was looking for.”

He successfully designed the motor and partnered with another inventor to improve the device’s soundbox. He also developed technologies to improve sound recording and disc production.

In 1900, he incorporated the Consolidated Talking Machine Company, which sold both gramophones and records. The following year, he was sued for patent infringement. He would win in the end, but only after being temporarily enjoined from using the word gramophone in any form.

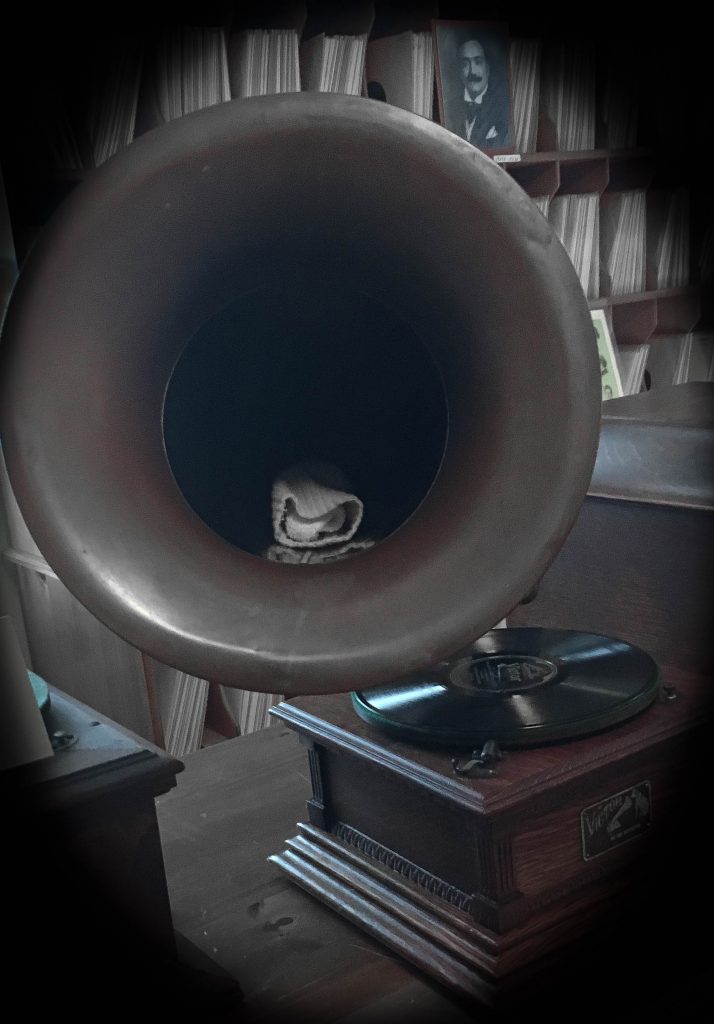

He registered the Victor trademark, reorganized the business as the Victor Talking Machine Company, and began selling phonographs called Victors. With a large external horn and no volume control, the sound of one of these bulky devices could only be regulated by stuffing something into its horn, typically a sock, popularizing the expression, “Put a sock in it!”

In 1906, the company introduced the Victrola, a refined device with the horn and turntable inside a cabinet, designed to function as a piece of furniture.

Models ranged from large, exquisitely crafted pieces to basic boxes where the speaker was bigger and everything else was smaller. There was still no volume control, and the sound had to be lowered by closing the cover, hence the expression, “Put a lid on it!”

Victor also signed and recorded some of the best known singers and musicians of the early 20th century, Enrico Caruso being among the foremost. The company was acquired by RCA in 1929, becoming RCA Victor.

From early on, Johnson was purposeful about branding his products. At the behest of his colleague Leon Douglass, the company invested heavily in expensive magazine advertising.

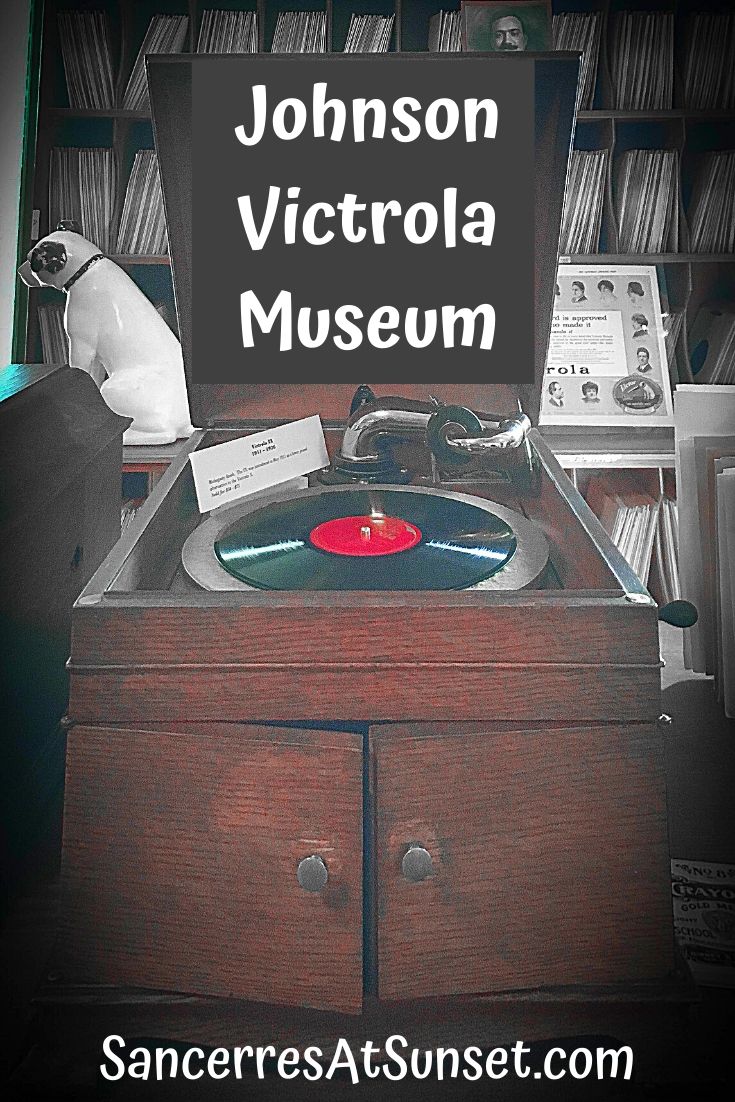

But its most recognized marketing symbol is Nipper, the RCA Victor terrier in the painting His Master’s Voice. The image became one of the most recognizable brand symbols in advertising history, its quaint charm highlighting the potential intimacy of recorded music.

The artist Francis Barraud first copyrighted his original version of the painting, Dog looking at and listening to a Phonograph, in 1899. The machine was an Edison-Bell, and Barraud first tried to sell his painting to that company, only to be rejected because “Dogs don’t listen to phonographs.”

Then William Barry Owen of the Gramophone Company in England offered to purchase the painting if Barraud would alter it to show a Berliner gramophone. Barraud complied, selling the revision and its copyright for £100. Emile Berliner then took out a U.S. copyright on it in 1900.

Johnson then trademarked it for the Consolidated Talking Machine Co, which became Victor the next year, and made it central to the company’s branding.

By 1902, Victor labels featured a drawing of the image; magazine ads reminded listeners to “Look for the dog.” But the marketing didn’t stop there. Victor sold an array of Nipper merch, ranging from stuffed animals to Lenox salt-and-pepper shakers.

The Johnson Victrola Museum reminds us how a single innovation can transform the way we experience the world. Eldridge R. Johnson’s vision brought music to the masses — combining technological discovery with business acumen to enrich daily life. A visit to the Museum is a chance to celebrate achievement — and to hear the voices of the past sing across the decades.

What to know before you go to the

Johnson Victrola Museum

The Johnson Victrola Museum is located at 375 South New Street in Dover, Delaware. It is free of charge to visit. Complimentary parking is available in an adjacent lot. Guided tours are casual and welcoming; the Museum is small and can be covered in an hour or two.

The four-star hotel closest to the Johnson Victrola Museum is

Bally’s Dover Casino Resort.

After my misspent youth as a wage worker, I’m having so much more fun as a blogger, helping other discerning travellers plan fun and fascinating journeys. Read more …