On February 4, 1777, General George Washington penned a letter to New York merchant Nathaniel Sackett.

This post contains affiliate links. For more information, click here.

Writing from Morristown, New Jersey, the General gave the merchant a daunting task:

Employ “those you may find necessary” to obtain “the earliest and best Intelligence of the designs of the enemy”.

In other words:

Set up a spy ring to help me defeat the world’s most powerful empire.

Unfortunately, Sackett didn’t work out well. The next year, Washington replaced him with Major Benjamin Tallmadge as director of military intelligence.

Tallmadge set up what became known as the Culper Spy Ring. The name was taken from Culpeper County in Washington’s home state of Virginia.

The International Spy Museum in Washington, D.C., recently revamped “Spying Launched a Nation“, its exhibit on the Culper Spy Ring. I had the chance to see it earlier this year.

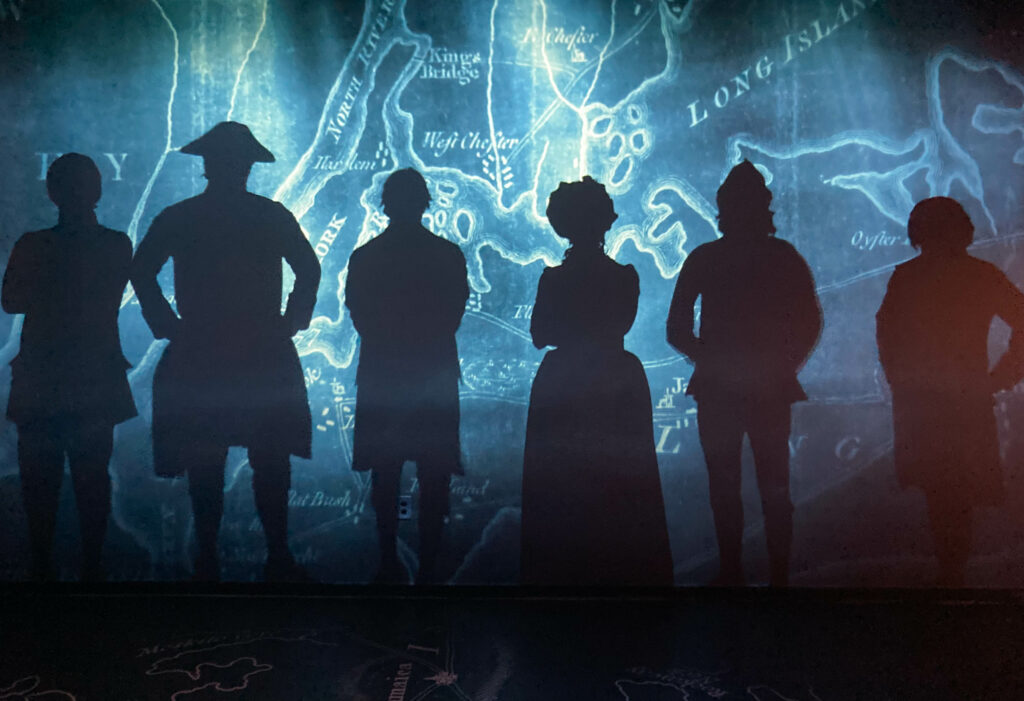

While I may disagree with the semantics (the signing of the Declaration of Independence launched our nation), the exhibit is fun. It’s an immersive experience that brings Washington and his spies to life with hologram-like imagery.

You stand in the middle of a big room while images of the spies and their efforts fill the walls all around and narration explains what’s going on. The authentic Washington letter softly glows from a secure display case.

The exhibit will appeal to anyone interested in tactical espionage or Revolutionary history.

Tallmadge recruited a handful of trusted fellow New Yorkers:

- Robert Townsend

- Austin Roe

- Caleb Brewster

- Abraham Woodhull

- Anna Strong

Their tactical tools included codes, dead drops, and a black petticoat.

Their mission was risky. The spies had to move in and out of British-controlled territory.

They relied on a sophisticated system meant to protect their identities, and thus their lives.

Posing as a Tory, Robert Townsend would move around New York City, gleaning information like British troop and ship movements.

Austin Roe would travel from Long Island to New York City, where Townsend owned a store.

At Townsend’s shop, Roe would pick up coded messages for Benjamin Tallmadge.

Roe would return to Long Island and hide the messages he received from Townsend on Abraham Woodhull’s farm.

Woodhull’s neighbor Anna Strong would hang a black petticoat on her clothesline as a signal to Caleb Brewster to pick up the messages.

Brewster would travel to Connecticut and deliver the messages to Tallmadge.

Tallmadge would pass the information to Washington in New York or New Jersey.

Even Washington didn’t know all the spies’ names. They used code names and even numbers. Washington’s code number was 711.

It worked. Not one was compromised during the five years that the Culper Spy Ring operated.

The Museum’s new exhibit emphasizes how the Culper Spy Ring foiled a British plot to attack the much-needed French forces sailing toward Newport, Rhode Island, under the Comte de Rochambeau in 1780.

Ironically, the French fleet might never have come to our aid if not for the most reviled spy in American history.

America’s underdog victory at the battles of Saratoga in 1777 convinced France that we could actually win the war for independence — and that they should strengthen their help to us.

And the hero of Saratoga was Benedict Arnold.

But three years later, Arnold would betray his country by conspiring with British spymaster Major John André to surrender the American fort at West Point.

Arnold got away. But thanks in part to Tallmadge’s reliable instincts, André was prevented from joining him. He was hanged on Washington’s orders, under the supervision of (my great-great-great-great-great-great-great-grandfather) Brig. General John Glover.

In that same year of 1780, France sent us a fleet carrying 6,000 troops. The Culper Spy Ring uncovered a British plan to attack the French fleet.

Washington responded with a disinformation campaign to convince the British that he was planning to attack New York City. It worked: The British diverted their fleet in order to reinforce their hold on New York.

The following year, America would win the decisive battle of Yorktown with the help of the French.

As one of Major André’s successors, Sir George Beckwith, noted after the War, “Washington did not really outfight the British. He simply out-spied us.”

Excellent hotels near the International Spy Museum include:

After my misspent youth as a wage worker, I’m having so much more fun as a blogger, helping other discerning travellers plan fun and fascinating journeys. Read more …