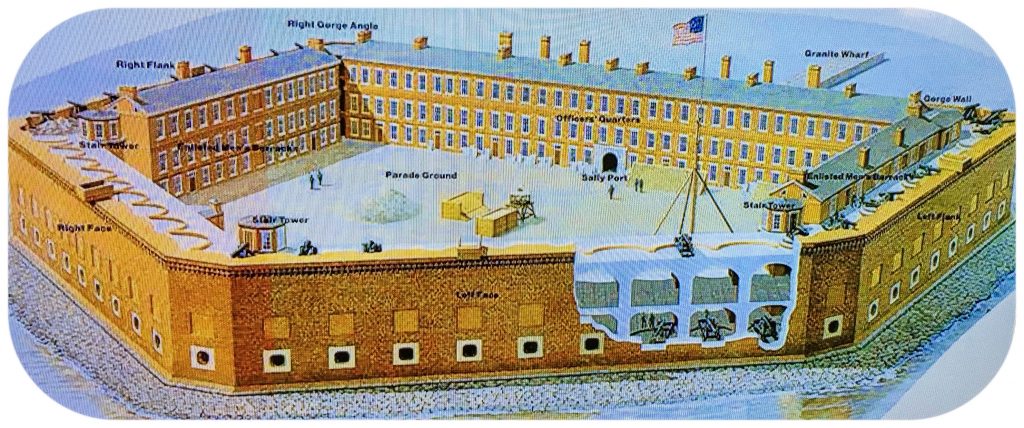

Charleston’s Battery and Rainbow Row faded from view as my travel companion and I sailed aboard the ferry toward Fort Sumter, perched on a small island in Charleston Harbor, site of the first battle in America’s bloodiest war. The five-sided Fort was planned during the 1820s, in the wake of the War of 1812. It was designed to withstand a naval attack of that era.

Our ferry had departed from Liberty Square in downtown Charleston, where a small museum teaches the factors that led up to the Battle of Fort Sumter and the Civil War.

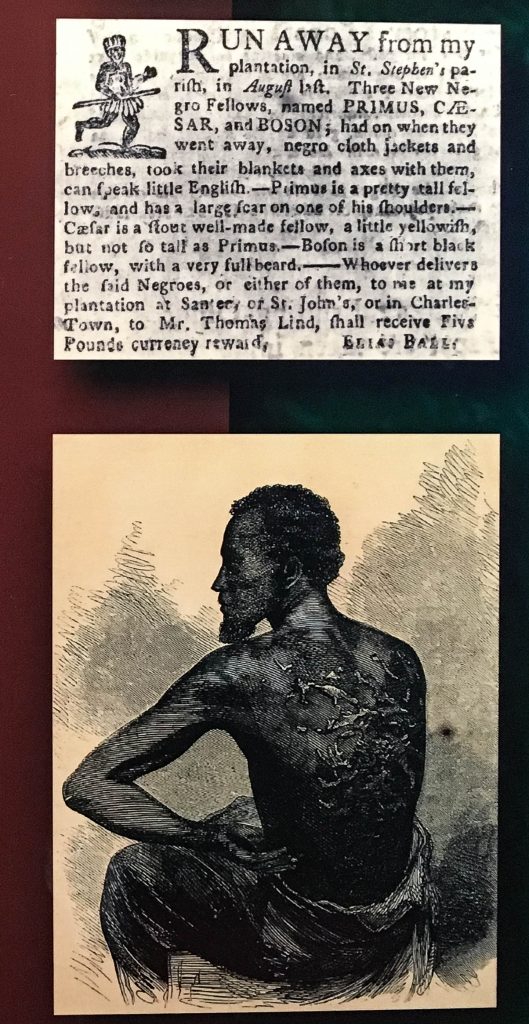

Conflict over slavery was part and parcel of the history of the United States, from the moment Thomas Jefferson was forced to delete its condemnation from our Declaration of Independence.

In 1820, the Missouri Compromise provided that Missouri would enter the Union as a slave state and that Maine would enter as a free state. In the future, southern states would come in with slavery, and northern states would enter free.

In 1850, California entered as a free state and markedly tipped the balance of power in Congress toward the North. To mollify the South, Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which required northerners to help return runaway slaves. In other words, there would be no truly free states, and no real “states’ rights”. A slave who escaped into the North remained at risk of being captured and forcibly returned to slavery.

This post contains affiliate links. For more information, click here.

This was a turning point, radicalizing public abolitionists from John Brown to Henry David Thoreau. Northerners were horrified that they could be legally compelled into complicity with so barbarous a practice.

In 1854, the Kansas-Nebraska Act paved the way for slave states in the West by allowing newly admitted Western states to determine their own free or slave status via popular vote.

In 1857, the Dred Scott Decision, one of the most appalling examples of judicial activism in the history of the Supreme Court, held that the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional, that “Negroes” — free or slave — were not citizens of the United States, and that slaves were legal property and their owners’ “right” to them was protected by the Fifth Amendment. North and South each viewed the decision as effectively making slavery legal throughout the United States.

In November 1860, Abraham Lincoln was elected President, having declared that he would oppose the expansion of slavery into new territories but would not attempt to overturn slavery where it already existed. He also insisted, “I believe this government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free.” By this point there were four million slaves in the United States.

In December, South Carolina seceded from the Union during a convention held in Charleston. Church bells rang; bonfires blazed, and fireworks filled the sky. Six more states soon seceded.

In February 1861, the Confederate States of America declared its independence in Montgomery, Alabama, and inaugurated its President Jefferson Davis.

But the presence of a Union fort in Charleston Harbor belied the Confederacy’s claim of its own sovereignty.

When we arrived on the island, a knowledgeable ranger gave an introductory talk.

In the early morning hours of April 12, 1861, envoys representing Confederate Brigadier General P.G.T. Beauregard notified Yankee Major Robert Anderson, the commanding officer at Fort Sumter, that the Confederacy would open fire on the Fort in one hour.

At 4:30 a.m., Beauregard kept his word. Fire filled the sky, and Charleston families rushed out to watch from across the water. The Civil War had begun.

At 7 a.m., Anderson ordered his second-in-command Captain Abner Doubleday (better misremembered as the man who invented baseball) to return fire.

At 1:30 p.m. on April 13, a Confederate marksman shot down the American flagstaff. Union soldiers quickly rigged a makeshift means to re-raise Old Glory.

After 34 hours of shelling, the Yankees were running out of ammunition. U.S.-Senator-turned-Confederate-soldier Louis Wigfall had himself rowed out to Fort Sumer under a white flag to deliver terms of surrender to Anderson: The Yankee soldiers would be permitted to salute the American flag, to evacuate the Fort armed and with honor, and to travel safely to the North.

Anderson ordered a white flag raised; the Confederates stopped shelling.

Then three more Confederate officers arrived on the island, and Anderson realized that Wigfall had no authority to negotiate. But shortly thereafter, acceptance of the Union surrender arrived from Beauregard.

Though the Fort was in ruins, there were no fatalities and only a few injuries on either side.

On April 14, Beauregard again kept his word: The Union soldiers were permitted a 100-gun salute to the Flag. But tragically, one cannon fired prematurely. A Union soldier was killed almost instantly, and another was fatally wounded. They would be the first of 620,000 American lives lost in the newly opened Civil War.

At 4:30 p.m., Anderson surrendered Fort Sumter to the South Carolina militia. Union soldiers stood in formation on the parade ground at Fort Sumter. Drummers beat out “Yankee Doodle Dandy”. The American flag flew above.

And then the Union soldiers boarded a steamboat, and the Stars and Bars and the Palmetto Guard replaced the Stars and Stripes.

After the talk, we were free to roam about the grounds. A second small but informative museum on the island teaches the history of Fort Sumter itself. But we spent much of our time outdoors, exploring the well-preserved ruins of the Fort, with its several cannon and thick walls, and enjoying the clear South Carolina day.

After about an hour, we boarded the ferry once again, and watched beautiful Charleston come clearer and clearer into view as she sailed back to Liberty Square.

After my misspent youth as a wage worker, I’m having so much more fun as a blogger, helping other discerning travellers plan fun and fascinating journeys. Read more …